In the previous blog, we considered John Trimble’s definition of effective writing: “Writing is the art of creating desired effects.” When applying that definition to persuasive writing, we have this definition:

Persuasive writing is the art of creating the desired effect of persuading readers.

Or, to shorten the definition . . .

Persuasive writing is the art of persuading readers.

So how exactly does a writer achieve persuasion? What is the anatomy of a persuasive essay? In short, you should think of writing as involving three aspects:

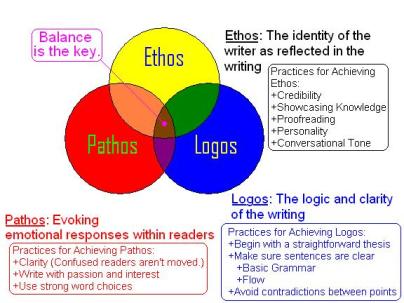

1. The writer (ethos)

2. The writing itself (logos)

3. The reader (pathos)

Every writer—or at least, every writer who wants to be successful—must consider all three of these writing aspects. They are all part of the rhetorical game. The writer wants to give a sense that she is an authority on the topic, or at least that she knows her topic well enough to write with some authority. At the same time, she does not want to come across as stodgy or inaccessible. Some personality (infused with a healthy smidgen of honesty) helps give the reader the sense that the writer is a friendly, sincere soul—but one who still knows her stuff. That’s ethos: the identity of the writer as transmitted through the writing.

What about the writing itself? Is it clearly written? Does the argument make sense? Does the argument ever contradict itself? Is the research cited pertinent to the writer’s arguments or points? That’s logos: the logic, unity, and essential clarity of the writing.

But even if the writer’s points are clear and well argued, who wants to read a dry, clinical list of pertinent data and formalized arguments? Writers win readers over not only by appealing to readers’ intellects, but also by evoking emotional responses. A good writer makes people think, but she also makes them feel. This aspect of style infuses otherwise dull facts and mute statistics with humanity and purpose. Emotional responses come in many forms. Does the writer want to make the reader laugh? Does she want readers to cry? Does she want her readers to be angry about the issue she’s discussing? Is she writing to shock her readers? Maybe she wants a bit of all four responses. That’s pathos: the emotional impact that the writing has on the reader.

The figure below shows these three essential aspects of writing. Consider the writing practices for achieving each effect. Also, while considering the image below, consider how there is an area where all three effects overlap. That area of complete overlap represents writing that balances logic (logos), character (ethos), and emotion (pathos). As a rule, that center of balance is where we want to be, although some writing situations call for us to emphasize some aspects over others. (For example, a lab report might be more logos-driven, while a personal response paper will emphasize a bit more ethos and pathos.)

The goal is to balance all three of these aspects in your writing. Experienced writers often achieve all three simultaneously. “Simultaneously? How is that done?” you might ask.

I’ll show you. Here’s an example from Bart Ehrman, one of my favorite non-fiction writers. These passages are drawn from the introduction to Ehrman’s book, God’s Problem: How the Bible Fails to Answer Our Most Important Question—Why We Suffer. Ehrman writes,

When I was young I always found the Christmas Eve service to be the most meaningful worship experience of the year. The sacred hymns and carols, the prayers and praises, the solemn readings from Scripture, the silent reflections on this most powerful of nights, when the divine Christ came into the world as a human infant . . .

What moved me most, however, was the congregational prayer, which did not come from the Book of Common Prayer but was written for the occasion, spoken loudly and clearly by a layperson standing in the aisle, his voice filling the vast space of the cavernous church around us. “You came into the darkness and made a difference,” he said. “Come into the darkness again.” This was the refrain of the prayer, repeated several times, in a deep and sonorous voice. And it brought tears to my eyes as I sat with bowed head, listening and thinking. But these were not tears of joy. They were tears of frustration. If God had come into the darkness with the advent of the Christ child, bringing salvation to the world, why is the world in such a state? Why doesn’t he enter into the darkness again? Where is the presence of God in this world of pain and misery? Why is the darkness so overwhelming? . . .

“You came into the darkness and you made a difference. Come into the darkness again.” Yes, I wanted to affirm this prayer, believe this prayer, commit myself to this prayer. But I couldn’t. The darkness is too deep, the suffering too intense, the divine absence too palpable. During the time that it took for this Christmas Eve service to conclude, more than 700 children in the world would have died of hunger; 250 others from drinking unsafe water; and nearly 300 other people from malaria. Not to mention the ones who had been raped, mutilated, tortured, dismembered, and murdered.

No matter our position on the existence of god, the sheer power of Ehrman’s prose is undeniable. It possesses a moving level of sincere frustration (ethos), and Ehrman presents some shocking numbers (logos) to give reasons for his frustration–and perhaps to transmit some of that frustration to the reader (pathos). In short, this writing represents a perfect fusion of all three writing aspects.

Four Essentials for Effective Writing

Here are John Trimble’s four essentials for winning readers. Consider how Ehrman’s writing in the passage above exhibits all four of these essentials:

1. Have something to say that’s worth their attention.

Ehrman’s discussion presents a topic that is relevant, for religious and non-religious readers alike: considering human suffering in light of popular religious beliefs.

2. Be sold on its validity and importance yourself so you can pitch it with conviction.

Can you feel Ehrman’s conviction in the writing–writing that is based on his life experience?

3. Furnish strong arguments that are well supported with concrete proof.

Consider the specific numbers that Ehrman presents. Notice that he presents a range of examples by discussing different forms of human suffering.

4. Use confident language—vigorous verbs, strong nouns, and assertive phrasing.

Verbs like affirm, repeated and mutilated are–without a doubt–vigorous verbs. Strong nouns include reflections, darkness, frustration, and misery. We hear assertive phrasing, for example, when Ehrman writes, “Yes, I wanted to affirm this prayer, believe this prayer, commit myself to this prayer. But I couldn’t.”

These are the elements of any successful writing strategy. Consider how Trimble’s four essentials are building blocks for producing ethos, logos, and pathos in our writing. Those three effects–those three dimensions of writing–create persuasion: the core “desired effect” of persuasive writing.

Next Up: All About Commas

One key to producing the desired effects of writing is having control over the movement and tone of a sentence. Punctuation is how writers do this.

Perhaps the most confusing punctuation technique is also the most frequent: the comma. The next part of The Writer’s Toolbox will help you understand the comma and its applications so that you can add this useful punctuation tool to your writing toolbox.

If you want to see the comma made simple, read on!

Here’s the link:

Works Cited

Ehrman, Bart D. God’s Problem: How the Bible Fails to Answer Our Most Important Question—Why We Suffer. New York: HarperCollins, 2008.

Trimble, John R. Writing with Style: Conversations on the Art of Writing. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2000.

Christopher Altman is passionate about bringing the art of effective writing to  everyday Americans. In addition to writing this blog, Mr. Altman produces and hosts The Writer’s Toolbox Podcast, and he is currently developing a number of book projects that examine the role of language in popular media and everyday life. His book, Myths We Learned in Grade School English, explores how adult writers can overcome the false writing rules learned in childhood. When he is not writing or teaching, Mr. Altman enjoys grilling out and savoring the mild summers of Central New York, where he is a professor of English at Onondaga Community College (Syracuse, NY).

everyday Americans. In addition to writing this blog, Mr. Altman produces and hosts The Writer’s Toolbox Podcast, and he is currently developing a number of book projects that examine the role of language in popular media and everyday life. His book, Myths We Learned in Grade School English, explores how adult writers can overcome the false writing rules learned in childhood. When he is not writing or teaching, Mr. Altman enjoys grilling out and savoring the mild summers of Central New York, where he is a professor of English at Onondaga Community College (Syracuse, NY).